how not to die summary

How Not To Die Summary | #1 FREE Review & Summary

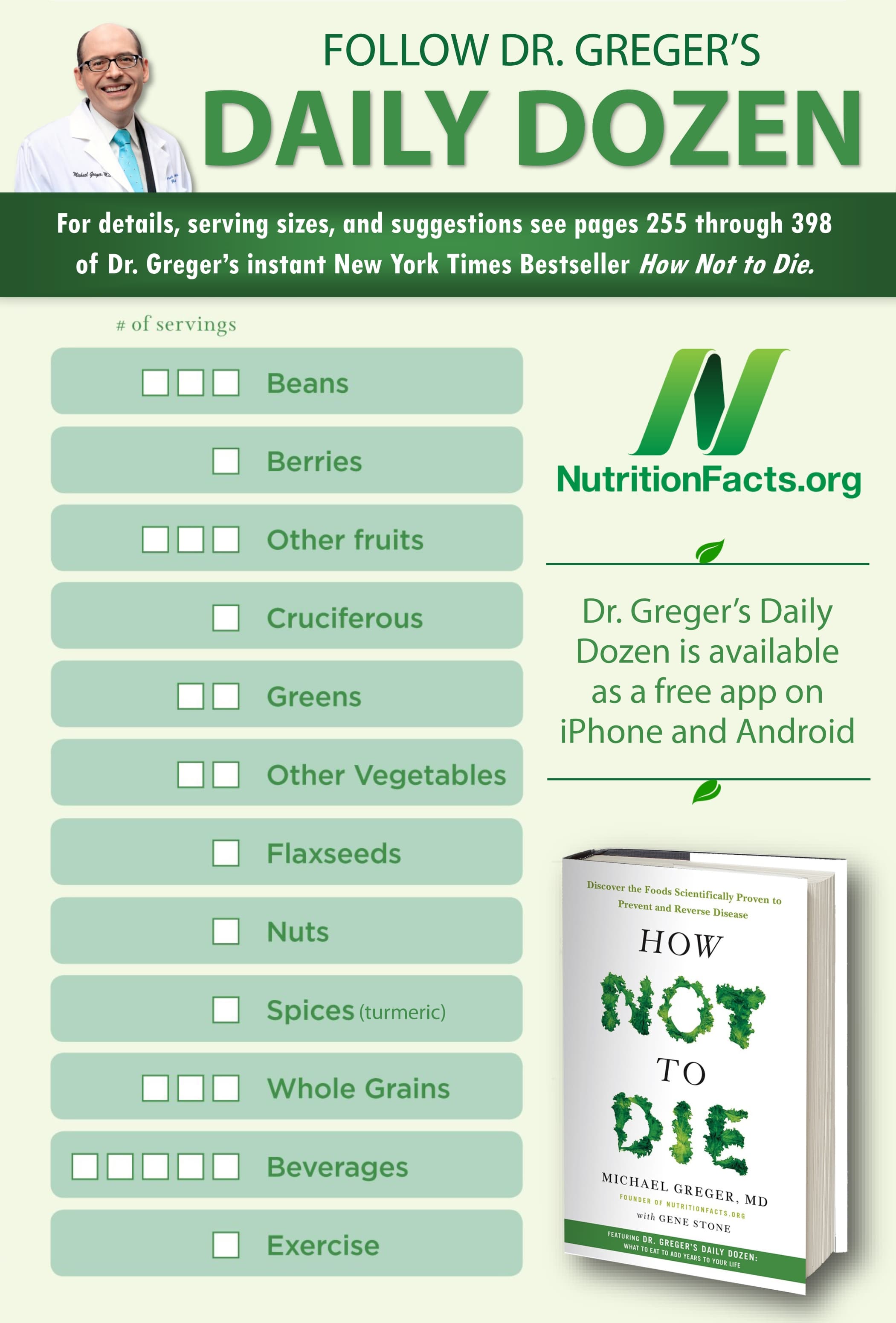

How Not To Die Summary | #1 FREE Review & SummaryNutrition "How not to die" by Dr. Michael Greger: A Critical Review As a child, Michael Greger saw his unfortunate grandmother from the heart return from the brink of promised death. His cure was Pritikin's diet with low fat content, and his return from Lazarus—a miracle for young Greger and the entourage of doctors who had sent her to his home to die— threw him on a mission to promote the healing power of food. Decades later, Greger has not diminished. Now an international professor, doctor and voice behind the science-parsing website, Greger recently added "best sales author" to his resume. Your book, How Not to Die, is a 562-page user guide to frustrate our biggest and most preventable killers. Your weapon of choice? The same one that saved your grandmother: a whole diet of food and plant. Like many books advocating for plant-based eating, how not to die paints nutritional science with a large brush, suspiciously without complications. Unprocessed vegetable foods are good, Greger hammers home, and everything else is a pest in the diet landscape. In his credit, Greger distinguishes plants from the less flexible vegan and vegetarian terms, and allows some humans to be human: "Don't hit if you really want to put edible bacon flavor candles on your birthday cake," he advises readers (p. 265). But science, he says, is clear: any raid outside the proverbial broccoli forest is for pleasure rather than for health. Despite its bias, How Not to Die contains treasures for members of any dietary persuasion. Their references are creepy, their reach is vast, and their games are not always bad. The book makes a comprehensive case for food as medicines and reassures readers that — far from the territory of the tinfoil hat — being careful with the "industrial-medical complex driven by profit" is justified. These advantages are almost sufficient to compensate for the greater responsibility of the book: its repeated distortion of research to adapt to ideology. What follows is a review of the most outstanding and hypothetical aspects of How Not to Die, with the premise that benefiting from the fortresses of the book requires sailing around its weaknesses. The readers who approach the book as a starting point instead of the incontrovertible truth will bear the best opportunity to do both. Cherry-Picked tests along How not to die, Greger distills a vast body of literature in a simple, black and white narrative — a feat only possible by collecting cherries, one of the most used fallacies in the world of nutrition. The selection of cherry is the act of selectively choosing or suppressing evidence to adapt to a predefined frame. In the case of Greger, that means presenting research when supporting plant-based feeding and ignoring it (or turning it creatively) when it does not. In many cases, observing Greger's chosen cherries is as simple as checking the book's statements against his quoted references. These pits are small but frequent. For example, as evidence that high oxalate vegetables are not a problem for kidney stones (a bold statement, given the wide acceptance of foods such as rhubarb and beets as risky for old stone), Greger quotes a paper that does not really look at the effects of high oxalate vegetables — only the total intake of vegetables (pages 170-171). Along with the assertion that "there is some concern that a greater intake of some vegetables ... could increase the risk of stone formation as it is known that they are rich in oxalato", the researchers suggest the inclusion of high oxalate vegetables in the diets of the participants might have diluted the positive results they found for the vegetables as a whole: "It is also possible that part of the intake of [sujetos] is in formal. In other words, Greger chose a study that could not only support his claim, but where the researchers suggested the opposite. Also, citing the EPIC-Oxford study as evidence that increases the risk of kidney stone, he states: "the subjects who did not eat meat at all had a significantly lower risk of being hospitalized for kidney stones, and for those who ate meat, the more they ate, the more associated risks" (p. 170). The study found that while heavy-duty eaters had the greatest risk of kidney stones, people who ate small amounts of meat better than those who ate nothing, a risk ratio of 0.52 for low-meat eaters versus 0.60 for vegetarians (). In other cases, Greger seems to redefine what "plant-based" means to collect more points for his home diet team. For example, it attributes an investment of the loss of diabetic vision to two years of plant-based food, but the program that it quotes is the Walter Kempner Rice Diet, whose foundation of , refined sugar and fruit juice barely supports the healing power of whole plants (p. 119) (p. 119). Later, he refers to the Rice Diet as evidence that "plant-based diets have been successful in treating chronic kidney failure"—without any warning that the highly processed and vegetable-free diet in question is a distant cry from which Greger recommends (p. 168) (p. 168). In other cases, Greger quotes abnormal studies whose only virtue, it seems, is that they claim their thesis. These cherries are difficult to detect even for the most dubious reference checker, since disconnection is not between the summary of Greger and the studies, but between studies and reality. As an example: when discussing cardiovascular disease, Greger challenges the idea that from fish they offer protection against the disease, citing a 2012 meta-analysis of fish oil trials and studies that advise people to take on the ocean's most fatty reward (p. 20) (p. 20). Greger writes that the researchers "did not find any protective benefits for general mortality, heart disease mortality, sudden cardiac death, heart attack or stroke" – effectively showing that it is, perhaps, only snake oil (p. 20). Catch her? This meta-analysis is one of the most criticized publications in the omega-3 sea, and other researchers did not waste time calling their mistakes. In an editorial letter, one critic noted that among studies included in meta-analysis, the average intake of omega-3 was 1.5 g per day, only half of the recommended amount to reduce the risk of heart disease (). Because so many studies used a clinically irrelevant dose, the analysis may have lost the cardioprotective effects seen in the upper omega-3 shots. Another respondent wrote that the results "must be interpreted cautiously" due to the numerous shortcomings of the study, including the use of an unnecessarily strict cut for statistical significance (P And another critic pointed out that any benefit of omega-3 supplementation would be difficult to prove among people who use statin drugs, which have pleiotropic effects that resemble the mechanisms involved with omega-3s (). This is important, since in several of the omega-3 trials without benefits, up to 85% of patients were in statins (). In the spirit of precision, Greger may have cited a more recent omega-3 review that avoids the errors of the previous study and — very intelligently — explains the inconsistent results between omega-3 trials (). In fact, the authors of this article encourage the consumption of two to three portions of oily fish per week, recommending that "physicists continue to recognize the benefits of omega-3 PUFAs to reduce cardiovascular risk in their high-risk patients" (). Maybe that's why Greger didn't mention it! Beyond misrepresenting individual studies (or quoting exactly questionable), How Not to Die presents slogs of pages through the false cherry orchard. In some cases, the complete discussions on a topic are based on incomplete evidence. Some of the most atrocious examples are: 1. Asthma and Animal Food When discussing how not to die from lung diseases, Greger offers a reference litany that shows that plant-based diets are the best way to breathe easily (literally), while animal products are the best way to breathe wheezy. But do your appointments support the claim that foods are only lung help if photosintthesize? In the summary of a population study covering 56 different countries, Greger states that adolescents who consume local diets with more starchy foods, vegetables and nuts were "significantally less likely to have chronic symptoms of sibilance, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and allergic eccema" (p. 39). That is technically accurate, but the study also found a less amenable association to the cause of the plant: total seafood, fresh fish and frozen fish were inversely associated with the three conditions. For the severe scourge, fish consumption was significantly protective. Describing another study of asthmatics in Taiwan, Greger recounts an association that arose between eggs and attacks of child asthma, wheezing, shortness of breath and exercise-induced cough (p. 39) (p. Although it is not false (as the correlation is not causal), the study also found that shellfish were negatively associated with the official diagnosis of asthma and dyspnea, the lack of breath of AKA. In fact, seafood rematized all other foods measured, including soy, fruit and vegetables, in the protection (in a mathematical sense) against asthma diagnosed and suspicious. Meanwhile, the vegetables—a fibrous star of the previous study— seemed to be useless in any account. Despite the radial silence in How Not to Die, these fish findings are hardly anomalies. Some studies suggest that omega-3 fats in seafood can reduce the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines and help to calm the troubled lungs (, , , , , , ). Perhaps the question, then, is not plant versus animal, but "albacore or albuterol?" Another lung assuager buried in Greger's references? Milk. Keeping the claim that "evil foods have been associated with increased risk of asthma," he describes a publication: "A study of more than one hundred thousand adults in India found that those who consumed meat daily, or even occasionally, were significantly more likely to suffer from asthma than those who excluded meat and eggs from their diets together" (p. 39). The study also found that, along with greens and fruit trees, milk consumption seemed to reduce the risk of asthma. As the researchers explained, "responsials who never consumed dairy/wilder products... were more likely to denounce asthma than those who consumed them every day." In fact, a milk-free diet was a risk factor along with unhealthy BMI, smoking and alcohol consumption. While dairy can also be a trigger for some asthmatics (although perhaps less often than commonly believed (, )), scientific literature points to a general protective effect of different dairy components. Some evidence suggests that dairy fat should obtain credit (), and raw milk seems powerfully protective against asthma and allergies — possibly due to heat-sensitive compounds in its fraction (, , , , , ). While many of the studies in question are limited by their observational nature, the idea that animal foods are cateral lung risks is difficult to justify—let alone. Dementia and DietAs with all the health problems discussed in How not to die, if the question is "disease", the answer is "plant foods". Greger makes a case to use plant-based feeding to overcome one of our most devastating cognitive ills: Alzheimer's disease. In discussing why genetics are not the final factor, being-all for Alzheimer's susceptibility, Greger quotes a role that shows that Africans who eat a traditional plant-based diet in Nigeria have far lower rates than African Americans in Indianapolis, where the omnivory reigns supreme (). That observation is true, and numerous migration studies confirm that moving to the United States is a great way to ruin your health. But the document, which is actually a broader analysis of Alzheimer's diet and risk in 11 different countries, discovered another important finding: fish, not just plants, is a guardian of the mind. This was particularly true between Europeans and Americans. In fact, when all the measurement variables — cereals, total calories, fats and fish — were analyzed, the brain benefits of cereals decreased, while fish took the lead as one.On the other hand, Greger quotes dietary changes to Japan and China — and the concurrent increase in Alzheimer's diagnosis — as more evidence that animal foods are a threat to the brain. He writes: "In Japan, the prevalence of Alzheimer's has increased in recent decades, thinking that it is due to the change of a traditional diet based on rice and vegetables to one that has triple dairy and six times meat... A similar tendency that unites diet and dementia was found in China" (page 94) (). In fact, in Japan, animal fat won the trophy for the most robust correlation with dementia, with the intake of animal fat that shoots at almost 600 percent between 1961 and 2008 (). Even so, even here, there could be more in history. A deeper analysis of Alzheimer's disease in East Asia shows that dementia rates gained artificial momentum when diagnosis criteria were resumed, leading to more diagnoses without much change in prevalence (). Researchers confirmed that "the per capita animal fat per day increased considerably in the last 50 years" — no doubt there. But after taking into account these diagnostic changes, the image changed considerably: "The positive relationship between total energy intake, animal fat and dementia prevalence disappeared after stratifying more new and greater diagnostic criteria." In other words, the link between animal food and dementia, at least in Asia, seemed to be a technical artifact rather than a reality. Greger also raises the theme of Seventh-day Adventists, whose religious mandate seems to help their brains. "Compared to those who eat meat more than four times a week," he writes, "those who have eaten vegetarian diets for thirty years or more had three times less risk of being demented" (p. 54). When reading the fine letter of the study, this trend only appeared in a matching analysis of a small number of people — 272. In the largest group of almost 3000 unparalleled adventists, there was no significant difference between meat eaters and meat avoiders in terms of risk of dementia. Similarly, in another study, looking at the elders of the same cohort, vegetarianism did not bless its adherents with any brain benefit: The consumption of meat showed neutral for cognitive decline (). And across the pond, vegetarians from the United Kingdom showed an astonishingly high mortality from neurological diseases compared to non-vegetarians, although the small size of the sample makes finding a bit faint (). But what about genetics? Here too, Greger serves a plant-based solution with a bowl of cherries chosen. In recent years, the E4 variant of apolipoprotein E — a major player in lipid transport — has emerged as a fearsome risk factor for Alzheimer's disease. In the West, being an apoE4 carrier can increase the chances of getting ten times or more Alzheimer's (). But as Greger points out, the connection of the apoE4-Alzheimer does not always remain beyond the industrialized world. Nigerians, for example, have a high prevalence of apoE4 but rocky background rates of Alzheimer's disease, a headhunter nigerian paradox (, ).The explanation? According to Greger, the traditional plant-based diet of Nigeria, rich in starches and vegetables, drops in all animal things, gives protection against genetic misfortune (p. 55). Greger speculates that the low cholesterol levels of Nigerians, in particular, are a saving grace, due to the potential role of abnormal cholesterol accumulation in the brain with Alzheimer's disease (page 55). For unfamiliar readers with apoE4 literature, Greger's explanation might sound convincing: plant-based diets break the chain that binds apoE4 to Alzheimer's disease. But globally, the argument is difficult to support. With few exceptions, the prevalence of apoE4 is greater among hunters and other indigenous groups: the Pygmies, the Inuit of Greenland, the Inuit of Alaska, the Khoi San, the Natives of Malaysia, the Aborigines of Australia, the Pyra and the Sámi of Northern Europe, all of which benefit from the apo. E4 as a tick Alzheimer's pump can have less to do with plant-based feeding and more than do with common features of hunter-recolector lifestyles: hunger cycles, high physical activity and unprocessed diets that are not necessarily limited to plants ().3. Soy and Breast Cancer When it comes to soy, the "90s dream" is alive in How not to die. Greger resurrectes a long-standing argument that this ex-superfood is kryptonite for breast cancer. Explaining the magic of soy, Greger points to his high concentration of isoflavones — a class of that interaction with estrogen receptors throughout the body (). Along with the most powerful human estrogen blocking within the breast tissue (a theoretical scourge for cancer growth), Greger proposes that soy isoflavones can reactivate our BRCA genes that repress cancer, which play a role in DNA repair and prevention of metastatic tumor spread (pages 195-196). To do the soy case, Greger provides several references suggesting that this lowly legume not only protects against breast cancer, but also increases survival and reduces recurrence in women who go shooting-soy-ho after diagnosis (pages 195-196) (, , , ). These quotations are not representative of the largest body of soy literature, and nowhere does Greger reveal how controversial, polarized and unclosed case-that is soy history (, ).For example, to support his statement that "soja seems to reduce the risk of breast cancer," Greger quotes a review of 11 observational studies that exclusively seek Japanese women (page 195). While researchers concluded that soy "possibly" decreases the risk of breast cancer in Japan, its wording was necessarily cautious: the protective effect was "suggested in some but not all studies" and was "limited to certain food items or subgroups" (). What's more, Japan's focus on the review casts great doubts about how global their findings are. Why? A common theme with soy research is that the protective effects seen in Asia—when they appear at all—do not do so through the Atlantic (). One document noted that four epidemiological meta-analysis unanimously concluded that the intake of isoflavone/soy food was inversely associated with the risk of breast cancer among Asian women, but this association did not exist among Western women ().Another meta-analysis that found a small protective effect of soy among Western women () had so many errors and limitations that their results were considered "non-believable". No one knows for sure, but one possibility is that certain genetic or microbiomic factors mediate the effects of soy. For example, around twice as many non-Asian Asians host the type of intestinal bacteria that convert isoflavones into equol — a metabolite that some researchers believe is responsible for the health benefits of soy (). Other theories include differences in the types of soy products consumed in Asia versus the West, residual confusion of other dietary and lifestyle variables, and a critical role for the early exposure of soy, in which child intake matters more than a late benefic of soy milk (). What about the ability of soy isoflavones to reactivate the so-called "caretaker" BRCA genes – in turn helping the body prevent breast cancer? Here, Greger quotes an in vitro study that suggests certain soy isoflavones may decrease DNA methylation in BRCA1 and BRCA2 — or, as Greger says, remove the "methyl stratum stick" that prevents these genes from doing their work (). Although interesting at a preliminary level (the researchers notice that their findings should be replicated and expanded before someone gets too excited), this study cannot promise that eating soy will have the same effect as incubating human cells along with isolated soy components in a laboratory. In addition, in vitro research battles never end well. Along with the recent discovery of BRCA, other cell studies (as well as tumor-injected rodent studies) have shown that soy isoflavones can improve the growth of breast cancer — raising the question of what contradictory finding is worth believing (, , ). That question, in fact, is at the critical point of the problem. Whether at the micro level (cell studies) or macrolevel (epidemiology), the research surrounding soy on the risk of cancer is highly conflictive, a Greger reality does not reveal. Sound Science As we have seen, Greger's references do not always support his claims, and his claims do not always match reality. But when they do, it would be smart to hear. Throughout How Not To Die, Greger explores many of the subjects ignored and myths in the world of nutrition—and in most cases, it represents the science of which he draws. In the midst of the growing fears of sugar, Greger helps—discussing the potential of fructose low doses to benefit the blood sugar, the lack of damage induced by the fruit for diabetics, and even a study in which 17 volunteers ate twenty for several months, with "no general adverse effects on body weight, blood pressure, insulin, cholesterol, and triglyceride levels" (p. He doubts about the fears surrounding legumes—sometimes malignant by their carbohydrate and antinutrient content—exploring their clinical effects on weight maintenance, insulin and cholesterol (p. 109). And, most importantly for the omivores, his penchant for the crack from time to time pauses enough to make room for a legitimate concern about the flesh. Two examples: 1. Carne Infections Beyond the dead horses, always beaten and , meat carries a legitimate risk that How not to die drags into the focus: human-transmissible virus. As Greger explains, many of humanity's most hated infections originated from animals, from goat tuberculosis to livestock measles (p. 79). But a growing body of evidence suggests that humans can acquire diseases not only to live near farm animals, but also to eat them. For many years, (UTIs) believed to originate from our own renegade strains E. coli finding its way from the intestine to the urethra. However, some researchers suspect that UTIs are a form of zoonosis, that is, an animal to human disease. Greger points out a clonal link recently discovered between E. coli in chicken and E. coli in human UTIs, which suggests that at least one source of infection is chicken meat that we handle or eat, not our resident bacteria (p. 94) (p. Worse still, chicken-derivated E. coli seems resistant to most antibiotics, which makes their infections particularly difficult to treat (p. 95) ().Pork can also serve as a source of multiple human diseases. Yersinia poisoning, almost universally linked to contaminated pig, brings more than a brief adventure with digestive problems: Greger points out that within a year of infection, Yersinia's victims have a greater risk of 47 times developing autoimmune arthritis, and it may also be more likely to develop Graves' disease (p. 96) (, ).Recently, the pig has also come under fire. Now considered potentially zoonotic, hepatitis E infection is routinely traced to the pig's liver and other pork products, with approximately one in ten pork livers from the American grocery store positively testing for the virus (page 148) (, ).Although most viruses (hepatitis E included) are deactivated by heat, Greger warns that hepatitis E can survive the rare temperatures reached in the heat. And when the virus survives, it means business. Areas with high consumption of pork have constantly raised rates of liver disease, and although that cannot prove cause and effect, Greger points out that the relationship between pig consumption and the death of liver disease "correlates as adjusted as per capita consumption of alcohol and liver fatalities" (p. 148). In a statistical sense, each devoured pork chop increases the risk of dying for liver cancer as much as drinking two cans of beer (page 148) (). All he said, animal infections are far from a strike against omnivory, per se. offer a lot of communicable diseases of his own (). And animals with the greatest risk of pathogen transmission are — in almost all cases — raised in commercial operations with overpopulation, unhygienic and poorly ventilated that serve as wells for pathogens (). Although How Not to Die is still very adjusted for any benefit of humanly elevated livestock, this is an area where quality can be a lifeline.2. Cooked meats and carcinogens Meat and heat make a tasty duo, but as Greger points out, poses some unique risks to animal food. In particular, he quotes what the Harvard Health Charter called meat preparation paradox: "Cooking care reduces the risk of getting food infections in depth, but cooking meat too thoroughly can increase the risk of food carcinogens" (p. 184). There are several of these food carcinogens, but the exclusive animal food is called heterocyclic amines (HCA). HCAs are formed when muscle meat — whether from creatures of the earth, the sea or the sky — is exposed at high temperatures, approximately 125-300 degrees C or 275-572 degrees F. Because a critical component of HCA development, it is found only in muscle tissue, even the most woven vegetables will not form HCAs (). As Greger explains, the HCAs were whimsically discovered in 1939 by an investigator who gave mice breast cancer for "painting their heads with roasted horse muscle extracts" (p. 184) (p. 184). In the decades since then, HCAs have proved to be a legitimate danger to the omnivores who like their high flesh in the "doted" spectrum. Greger provides a solid list of studies—decently conducted, described fairly—that show a link between meat and high-temperature breast cancer, colon cancer, esophagus cancer, lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, and stomach cancer (p. 184) (p. In fact, the cooking method seems to be an important mediator for the association between meat and several cancers that arise in epidemiological studies, with the grill, fried and well-made risk of significantly increased meat (). And the link is far from observatory. PhIP, a well studied type of HCA, has proven to stimulate growth of breast cancer almost as powerful as estrogen, while also acts as a "complete" carcinogen that can initiate, promote and spread cancer within the body (page 185) (). The solution for meat eaters? A revamp cooking method. Greger explains that roast, skillet, grill and baking are all common HCA manufacturers, and the longer a food hangs in the heat, the more HCA emerges (p. 185). The low-temperature kitchen, on the other hand, appears. In what could be the closest thing to an animal food aval offered, Greger writes, "Eating boiled meat is probably the safest" (p. 184). Conclusion Greger's goal, provoked in his youth and galvanized in the course of his medical career, is to avoid intermediaries and feed important information — and often life-saving — to the public. "With the democratization of information, doctors no longer have a monopoly as guardians of knowledge about health," he writes. "I realize that it can be more effective to empower individuals directly" (page xii). And that's what How Not to Die finally accomplishes. While the biases of the book prevent it from being a fully cave-free resource, it offers more than enough forage to keep health seekers questioned and committed. Readers willing to listen when the facts are questioned and verified when the skeptic will gain much from the passionate, though imperfect, take. Read this now.

How Not To Die Summary | #1 FREE Review & Summary

How Not to Die Summary: 11 Best Lessons from Dr. Michael Greger

Amazon.com: Summary of How Not To Die By Michael Greger MD (9781976836657): Concise Reading, Concise Reading: Books

Summary of How Not To Die By Michael Greger MD by Concise Reading

How Not to Die Summary | PDF | Free Audiobook

How Not to Die Book Summary by Michael Greger

HOW NOT TO DIE BY MICHAEL GREGER M.D. ANIMATED SUMMARY | by Health Wealth Love | Medium

How Not To Die Summary and Review - Four Minute Books

How Not to Die: An Animated Summary | NutritionFacts.org

Summary of How Not to Die by Michael Greger M.D.: Discover the Foods Scientifically Proven to Prevent and Reverse Disease: Books, Brighten: 9798637634941: Amazon.com: Books

Summary of How Not to Die: From MICHAEL GREGER M.D. by Summary Station

Summary of How Not to Die: Discover the Foods Scientifically Proven to Prevent and Reverse Disease by Michael Greger Md & Gene Stone - Audiolibro - Abbey Beathan - Storytel

Summary: How Not To Die by Dr. Michael Greger eBook by Alpha Minds | Rakuten Kobo

![PDF] The How Not to Die Cookbook: 100+ Recipes to Help Prevent and Reverse Disease Download PDF] The How Not to Die Cookbook: 100+ Recipes to Help Prevent and Reverse Disease Download](https://pdfget.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/PDF-EPUB-The-How-Not-to-Die-Cookbook-100-Recipes-to-Help-Prevent-and-Reverse-Disease-by-Michael-Greger-Download.jpg)

PDF] The How Not to Die Cookbook: 100+ Recipes to Help Prevent and Reverse Disease Download

How To Not Die Book - How to Wiki 89

Summary of How Not To Die By Michael Greger, M.D. with Gene Stone by Project Inspiration

How Not To Die by Dr. Michael Greger | Summary and Quotes - On Books | Book Podcast

How Not to Die by Michael Greger MD, Gene Stone - Book Summary - Audiolibro - Flashbooks - Storytel

![NO COST]~ Summary How Not To Die by Dr Michael Greger Discover the … NO COST]~ Summary How Not To Die by Dr Michael Greger Discover the …](https://cdn.slidesharecdn.com/ss_thumbnails/summaryhownottodiebydrmichaelgregerdiscoverthefoodsscientificallyprovento-191212075311-thumbnail-4.jpg?cb=1576137228)

NO COST]~ Summary How Not To Die by Dr Michael Greger Discover the …

Read How Not to Die | Summary Online by Summary Station | Books

Michael Greger: How Not to Die: Discover the Proven to Prevent and Reverse Disease Book Summary | Bestbookbits | Daily Book Summaries | Written | Video | Audio

Summary Of How Not To Die By Michael Greger M.D. Discover The Foods Scientifically Proven To Preven by harmonywunsch - issuu

SUMMARY OF How Not to Die | Discover the Foods Scientifically Proven to Prevent and Reverse Disease By Michael Greger, MD, and Gene Stone eBook by CTPrint - 1230003693506 | Rakuten Kobo United States

Amazon.com: Summary of How Not to Die: Discover the Foods Scientifically Proven to Prevent and Reverse Disease by Michael Greger Md & Gene Stone (9781690406662): Beathan, Abbey: Books

How Not to Die from Diabetes SUMMARY | Avoid Diabetes (How NOT to Die - Dr. Michael Greger) - YouTube

Read Summary of How Not to Die by Dr. Michael Greger Online by SpeedReader Summaries | Books

![download]_p.d.f))^@@ Summary How Not To Die by Dr Michael Greger Dis… download]_p.d.f))^@@ Summary How Not To Die by Dr Michael Greger Dis…](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/summaryhownottodiebydrmichaelgregerdiscoverthefoodsscientificallyprovento-191101082617/95/downloadpdf-summary-how-not-to-die-by-dr-michael-greger-discover-the-foods-scientifically-proven-to-prevent-and-reverse-disease-readonline-1-638.jpg?cb=1572596824)

download]_p.d.f))^@@ Summary How Not To Die by Dr Michael Greger Dis…

Babelcube – Summary & study guide - how not to die

How Not To Die - Dr. Michael Greger (BOOK) - YouTube

Amazon.com: Summary and Analysis of How Not to Die: Discover the Foods Scientifically Proven to Prevent and Reverse Disease By Michael Greger, MD, and Gene Stone eBook: Acesprint: Kindle Store

Summary of How Not to Die by Michael Greger, MD, with Gene Stone Audiobook | Summary Station | Audible.co.uk

How Not to Die by Michael Greger MD, Gene Stone - Book Summary: Discover the Foods Scientifically Proven to Prevent and Reverse Disease on Apple Books

Summary of How Not to Die by Michael Greger M.D.: Buy Summary of How Not to Die by Michael Greger M.D. by Bookhabits at Low Price in India | Flipkart.com

Summary: How Not to Die by Michael Greger MD by Quality Summaries | Audiobook | Audible.com

Summary of How Not To Die: by Michael Greger Includes Analysis, Book by Instaread Summaries (Paperback) | www.chapters.indigo.ca

How Not to Die by Dr. Michael Greger - Animated Book Summary - YouTube

Summary of How Not to Die by Michael Greger M.D (Genius Reads): Reads, Genius: 9798610297767: Amazon.com: Books

Summary of Michael Greger's How Not to Die : Discover the Foods Scientifically Proven to Prevent and Reverse Disease - Walmart.com - Walmart.com

How Not to Diet Book Summary (PDF) by Michael Greger, M.D. - Two Minute Books

Posting Komentar untuk "how not to die summary"